For other persons named Stuart Hall, see. Stuart Hall Born Stuart Henry McPhail Hall ( 1932-02-03)3 February 1932, Died 10 February 2014 ( 2014-02-10) (aged 82), Alma mater Known for Founder of, Scientific career Fields, Institutions Influences, Stuart McPhail Hall, (3 February 1932 – 10 February 2014) was a Jamaican-born, political activist and who lived and worked in the from 1951. Hall, along with and, was one of the founding figures of the school of thought that is now known as or The. In the 1950s Hall was a founder of the influential. At the invitation of Hoggart, Hall joined the at in 1964. Hall took over from Hoggart as acting director of the Centre in 1968, became its director in 1972, and remained there until 1979. While at the Centre, Hall is credited with playing a role in expanding the scope of cultural studies to deal with race and gender, and with helping to incorporate new ideas derived from the work of French theorists like Michel Foucault.

Hall left the centre in 1979 to become a professor of sociology at the. He was President of the 1995–97. Hall retired from the in 1997 and was a. British newspaper called him 'one of the country's leading cultural theorists'. Hall was also involved in the. Movie directors such as and also see him as one of their heroes. Hall was married to, a feminist professor of modern British history.

Contents. Biography Stuart Hall was born in, into a middle-class Jamaican family of African, British and likely Indian descent. In Jamaica he attended, receiving an education modelled after the. In an interview Hall describes himself as a 'bright, promising scholar' in these years and his formal education as 'a very 'classical' education; very good but in very formal academic terms.' With the help of sympathetic teachers, he expanded his education to include ', and some of the surrounding literature and modern poetry,' as well as '.' Hall's later works reveal that growing up in the of the colonial West Indies, where he was of darker skin than much of his family, had a profound effect on his views of the world. In 1951 Hall won a to at the, where he studied English and obtained an, becoming part of the, the first large-scale immigration of, as that community was then known.

He continued his studies at Oxford by beginning a Ph.D. On but, galvanised particularly by the 1956 (which saw many thousands of members leave the (CPGB) and look for alternatives to previous orthodoxies) and, abandoned this in 1957 or 1958 to focus on his political work.

In 1957, he joined the (CND) and it was on a CND march that he met his future wife. From 1958 to 1960, Hall worked as a teacher in a London and in adult education, and in 1964 married, concluding around this time that he was unlikely to return permanently to the Caribbean.

Cultural studies - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Cultural studies is a field of theoretically, politically, and empirically engaged cultural analysis that was. Stuart Hall and Cultural Studies: Decoding Cultural. In talking about the intellectual roots of cultural studies, Stuart Hall. There are at least two.

After working on the Universities and Left Review during his time at Oxford, Hall joined, and others to merge it with, launching the New Left Review in 1960 with Hall named as the founding editor. In 1958, the same group, with, launched the in as a meeting-place for left-wingers. Hall left the board of the New Left Review in 1961 or 1962.

Hall's academic career took off after he co-wrote in 1964 with of the British Film Institute (BFI) 'one of the first books to make the case for the serious study of film as entertainment', The Popular Arts. As a direct result, invited Hall to join the at the, initially as a research fellow and initially at Hoggart's own expense. In 1968 Hall became director of the Centre. He wrote a number of influential articles in the years that followed, including Situating Marx: Evaluations and Departures (1972) and Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse (1973). He also contributed to the book Policing the Crisis (1978) and coedited the influential Resistance Through Rituals (1975). After his appointment as a professor of sociology at the (OU) in 1979, Hall published further influential books, including The Hard Road to Renewal (1988), Formations of Modernity (1992), Questions of Cultural Identity (1996) and Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (1997). Through the 1970s and 1980s, Hall was closely associated with the journal; in 1995, he was a founding editor of.

Hall retired from the Open University in 1997. He was elected (FBA) in 2005 and received the 's Princess Margriet Award in 2008. He died on 10 February 2014, from complications following kidney failure a week after his 82nd birthday.

By the time of his death, he was widely known as the 'godfather of multiculturalism'. Ideas Hall's work covers issues of and, taking a post- stance.

He regards language-use as operating within a framework of, and politics/economics. This view presents people as producers and consumers of culture at the same time. (Hegemony, in Gramscian theory, refers to the socio-cultural production of 'consent' and 'coercion'.) For Hall, culture was not something to simply appreciate or study, but a 'critical site of social action and intervention, where power relations are both established and potentially unsettled'. Hall became one of the main proponents of, and developed of encoding and decoding.

This approach to focuses on the scope for negotiation and opposition on the part of the audience. This means that the audience does not simply passively accept a text—social control. Crime statistics, in Hall's view, are often manipulated for political and economic purposes. Moral panics (e.g. Over mugging) could thereby be ignited in order to create public support for the need to 'police the crisis'. The media play a central role in the 'social production of news' in order to reap the rewards of lurid crime stories.

Hall's works, such as studies showing the link between and, have a reputation as influential, and serve as important foundational texts for contemporary. He also widely discussed notions of, and, particularly in the creation of the politics of Black diasporic identities. Hall believed identity to be an ongoing product of history and culture, rather than a finished product. Hall's political influence extended to the, perhaps related to the influential articles he wrote for the CPGB's theoretical journal ( MT) that challenged the left's views of markets and general organisational and political conservatism.

This discourse had a profound impact on the Labour Party under both and, although Hall later decried as operating on 'terrain defined by Thatcherism'. Encoding and decoding model. Main article: Hall presented his encoding and decoding philosophy in various publications and at several oral events across his career. The first was in ' (1973), a paper he wrote for the Council of Europe Colloquy on 'Training in the Critical Readings of Television Language' organised by the Council & the Centre for Mass Communication Research at the. It was produced for students at the, which explains: 'largely accounts for the provisional feel of the text and its ‘incompleteness’'.

In 1974 the paper was presented at a symposium on Broadcasters and the Audience in. Hall also presented his encoding and decoding model in 'Encoding/Decoding' in Culture, Media, Language in 1980.

The time difference between Hall's first publication on encoding and decoding in 1973 and his 1980 publication is highlighted by several critics. Of particular note is Hall's transition from the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies to the.

Hall had a major influence on cultural studies, and many of the terms his texts set forth continue to be used in the field today. His 1973 text is viewed as marking a turning point in Hall's research, towards structuralism and provides insight into some of the main theoretical developments Hall was exploring during his time at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall takes a approach and builds on the work of and.

The essay takes up and challenges longheld assumptions on how media messages are produced, circulated and consumed, proposing a new theory of communication. 'The ‘object’ of production practices and structures in television is the production of a message: that is, a sign-vehicle or rather sign-vehicles of a specific kind organized, like any other form of communication or language, through the operation of codes, within the syntagmatic chains of a discourse'.

According to Hall, 'a message must be perceived as meaningful discourse and be meaningfully de-coded before it has an effect, a use, or satisfies a need'. There are four codes of the. The first way of encoding is the dominant (i.e. Hegemonic) code. This is the code the encoder expects the decoder to recognize and decode. 'When the viewer takes the connoted meaning full and straight and decodes the message in terms of the reference-code in which it has been coded, it operates inside the dominant code'.

The second way of encoding is the professional code. It operates in tandem with the dominant code. 'It serves to reproduce the dominant definitions precisely by bracketing the hegemonic quality, and operating with professional codings which relate to such questions as visual quality, news and presentational values, televisual quality, ‘professionalism’ etc.' The third way of encoding is the negotiated code. 'It acknowledges the legitimacy of the hegemonic definitions to make the grand significations, while, at a more restricted, situational level, it makes its own ground-rules, it operates with ‘exceptions’ to the rule'.

The fourth way of encoding is the oppositional code also known as the globally contrary code. 'It is possible for a viewer perfectly to understand both the literal and connotative inflection given to an event, but to determine to decode the message in a globally contrary way.' 'Before this message can have an ‘effect’ (however defined), or satisfy a ‘need’ or be put to a ‘use’, it must first be perceived as a meaningful discourse and meaningfully de-coded.' Hall challenged all four components of the mass communications model. He argues that (i) meaning is not simply fixed or determined by the sender; (ii) the message is never transparent; and (iii) the audience is not a passive recipient of meaning. For example, a documentary film on asylum seekers that aims to provide a sympathetic account of their plight, does not guarantee that audiences will decode it to feel sympathetic towards the asylum seekers.

Despite its being realistic and recounting facts, the documentary form itself must still communicate through a sign system (the aural-visual signs of TV) that simultaneously distorts the intentions of producers and evokes contradictory feelings in the audience. Distortion is built into the system, rather than being a 'failure' of the producer or viewer. There is a 'lack of fit', Hall argues, 'between the two sides in the communicative exchange'. That is, between the moment of the production of the message ('encoding') and the moment of its reception ('decoding').

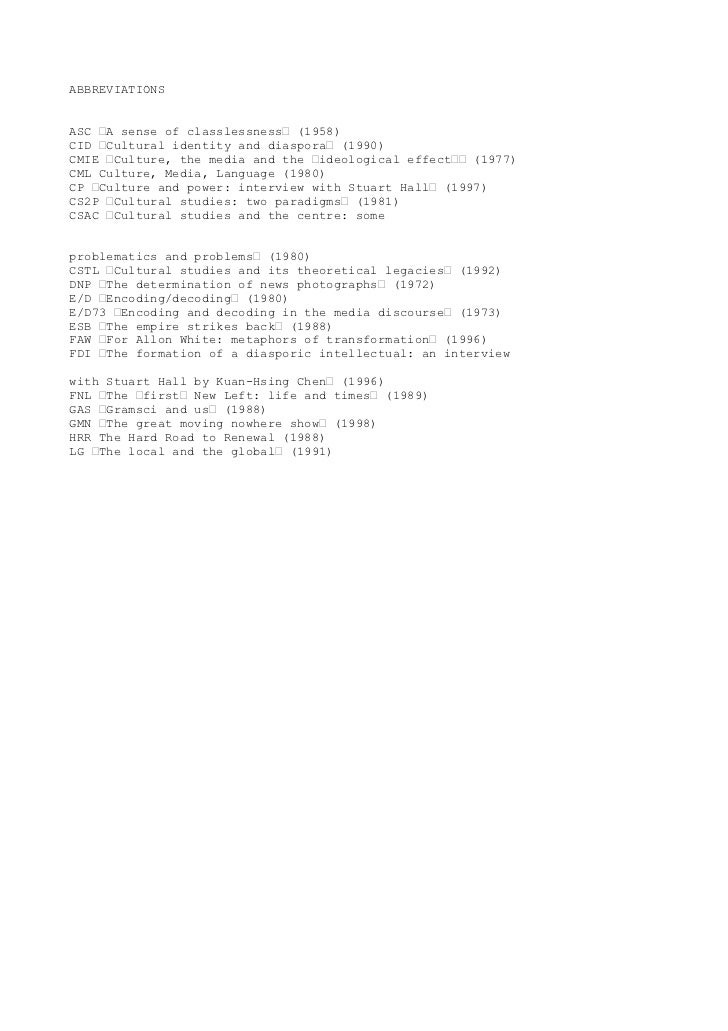

In 'Encoding/decoding', Hall suggests media messages accrue a common-sense status in part through their performative nature. Through the repeated performance, staging or telling of the narrative of ' (as an example; but there are others like it within the media) a culturally specific interpretation becomes not only simply plausible and universal, but is elevated to 'common-sense'. Publications (incomplete) 1960s. Hall, Stuart (March–April 1960).

New Left Review. New Left Review. Hall, Stuart (January–February 1961). New Left Review. New Left Review. I (7): 50–51. Hall, Stuart (March–April 1961).

New Left Review. New Left Review. I (8): 47–48. Hall, Stuart; (July–August 1961). New Left Review. New Left Review.

I (10): 1–15. Hall, Stuart; Whannell, Paddy (1964).

The Popular Arts. London: Hutchinson Educational. Hall, Stuart (1968). The Hippies: an American 'moment'. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. 1970s. Hall, Stuart (1971).

Deviancy, Politics and the Media. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall, Stuart (1971). 'Life and Death of Picture Post', Cambridge Review, vol.

Hall, Stuart; P. Walton (1972).

Situating Marx: Evaluations and Departures. London: Human Context Books. Hall, Stuart (1972). 'The Social Eye of Picture Post', Working Papers in Cultural Studies, no. 2, pp. 71–120. Hall, Stuart (1973).

Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Hall, Stuart (1973). A ‘Reading’ of Marx's 1857 Introduction to the Grundrisse. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies.

Hall, Stuart (1974). 'Marx's Notes on Method: A ‘Reading’ of the ‘1857 Introduction’', Working Papers in Cultural Studies, no. Hall, Stuart; T. Jefferson (1976), Resistance Through Rituals, Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain. London: HarperCollinsAcademic. Hall, Stuart (1977).

'Journalism of the air under Review'. Journalism Studies Review. 1 (1): 43–45.

Hall, Stuart; Critcher, C.; Jefferson, T.; Clarke, J.; Roberts, B. (1978) Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. London: Macmillan. London: Macmillan Press. (paperback) (hardbound).

Cultural Studies Theory

Hall, Stuart (January 1979). Amiel and Melburn Collections: 14–20. 1980s. Hall, Stuart (1980). 'Encoding / Decoding.' Willis (eds).

Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972–79. London: Hutchinson, pp. 128–138. Hall, Stuart (January 1980). 2 (1): 57–72. Hall, Stuart (1981). 'Notes on Deconstructing the Popular'. In People's History and Socialist Theory.

London: Routledge. Hall, Stuart; P. Scraton (1981).

'Law, Class and Control'. Fitzgerald, G. McLennan & J. Pawson (eds).

Crime and Society, London: RKP. Hall, Stuart (1988). The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left. London: Verso. Hall, Stuart (June 1986).

10 (2): 5–27. Hall, Stuart (June 1986). Journal of Communication Inquiry. 10 (2): 28–44.

Hall, Stuart; (July 1986). Marxism Today. Amiel and Melburn Collections: 10–14. 1990s. Hall, Stuart;; McGrew, Anthony (1992). Modernity and its futures. Cambridge: Polity Press in association with the Open University.

Hall, Stuart (1992), 'The question of cultural identity', in Hall, Stuart; Held, David; McGrew, Anthony, Modernity and its futures, Cambridge: Polity Press in association with the Open University, pp. 274–316,. Hall, Stuart (Summer 1996)., issue: Heroes and heroines. Hall, Stuart (1997).

Representation: cultural representations and signifying practices. London Thousand Oaks, California: Sage in association with the Open University. Hall, Stuart (1997), 'The local and the global: globalization and ethnicity', in; Mufti, Aamir;, Dangerous liaisons: gender, nation, and postcolonial perspectives, Minnesota, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 173–187,. Hall, Stuart (January–February 1997). New Left Review. 2000s.

Hall, Stuart (2001), 'Foucault: Power, knowledge and discourse', in; Taylor, Stephanie; Yates, Simeon J., Discourse Theory and Practice: a reader, D843 Course: Discourse Analysis, London Thousand Oaks California: in association with the, pp. 72–80,. 2010s. Hall, Stuart (2011)., special issue: Queer Adventures in Cultural Studies. 25 (2): 139–146.

Hall, Stuart (2011). Cultural Studies.

25 (6): 705–728. Hall, Stuart; Evans, Jessica; Nixon, Sean (2013) 1997. Representation (2nd ed.). London: Sage in association with The Open University. Hall, Stuart (2016). Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History.

Slack, Jennifer and Lawrence Grossberg, eds. Duke University Press. Hall, Stuart (2017). Selected Political Writings: The Great Moving Right Show and other essays. London: Lawrence & Wishart. Hall, Stuart (with Bill Schwartz) (2017). Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands.

London: Allen Lane; Durham: Duke University Press. Legacy. The, 's reference library at in, London, founded in 2007, is named after Stuart Hall, who was the chair of the board of InIVA for many years.

In November 2014 a week-long celebration of Stuart Hall's achievements was held at the 's, where on 28 November the new Academic Building was renamed in his honour, as the Professor Stuart Hall building (PSH). The establishment of the Stuart Hall Foundation in his memory and to continue his life's work was announced in December 2014. Film Hall was a presenter of a seven-part television series entitled Redemption Song — made by Barraclough Carey Productions, and transmitted on, between 30 June and 12 August 1991 — in which he examined the elements that make up the Caribbean, looking at the turbulent history of the islands and interviewing people who live there today. The series episodes were as follows:. 'Shades of Freedom'.

'Following Fidel'. 'Worlds Apart' (28 July 1991).

'La Grande Illusion' (21 July 1991). 'Paradise Lost' (14 July 1991). 'Out of Africa' (7 July 1991).

'Iron in the Soul' (30 June 1991) Hall's lectures have been turned into several videos distributed by the Media Education Foundation:. (1997). Produced a film based on a long interview between journalist and Stuart Hall called Personally Speaking (2009). Hall is the subject of two films directed by, entitled (2012) and (2013). The first film was shown (26 October 2013 – 23 March 2014) at, London, while the second is now available on DVD.

The Stuart Hall Project was composed of clips drawn from more than 100 hours of archival footage of Hall woven together over the music of jazz artist, who was an inspiration to both Hall and Akomfrah. The film's structure is composed of multiple strands. There is a chronological grounding in historical events, such as the, Vietnam War, and the, along with reflections by Hall on his experiences as an immigrant from the Caribbean to Britain. Another historical event that was vital to the film, was the showing there of the occasioned by the murder of a Black British man; these protests showed the presence of a Black community within England. When discussing the Caribbean, Hall discusses the idea of hybridity and he states that the Caribbean is the home of hybridity.

There are also voiceovers and interviews offered without a specific temporal grounding in the film that nonetheless give the viewer greater insights into Hall and his philosophy. Along with the voiceovers and interviews, embedded in the film are also Hall's personal achievements; this is extremely rare, as there are no traditional archives of those Caribbean peoples moulded by the experience. The film can be viewed as a more pointedly focused take on the, those who migrated from the Caribbean to Britain in the years immediately following. Hall, himself a member of this generation, exposed the less glamorous truth underlying the British Empire experience for Caribbean people, contrasting West Indian migrant expectations with the often harsher reality encountered on arriving in the Mother Country. A central theme in the film is Diasporic belonging. Hall himself confronted his own identity within both British and Caribbean communities and at one point in the film, remarks: 'Britain is my home, but I am not English.' IMDb calls the film 'a roller coaster ride through the upheavals, struggles and turning points that made the 20th century the century of campaigning, and of global political and cultural change.'

In August 2012, Professor conducted an interview with Hall that touched on a number of themes and issues in cultural studies. Book. (2016). Stuart Hall, cultural studies and the rise of Black and Asian British art. Has also written an article in tribute to Hall:.

14 February 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014. References.

Procter, James (2004), Stuart Hall, Routledge Critical Thinkers. ^ David Morley and Bill Schwarz, The Guardian (London), 10 February 2014. Schulman, Norman., Canadian Journal of Communication, Vol. Chen, Kuan-Hsing. 'The Formation of a Diasporic Intellectual: An interview with Stuart Hall,' collected in David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen (eds), Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, New York: Routledge, 1996.

'Stuart Hall: Culture and Power,' 16 March 2009 at the., Radical Philosophy, November/December 1998. ^ Tim Adams (22 September 2007). The Observer. Retrieved 17 February 2014. Isaac Julien, BFI, 12 February 2014. ^ Grant Farred, Research in African Literatures, 27.4 (Winter 1996), 28–48 (p. Kuan-Hsing, 1996, pp.

^ Tanya Lewis, Imperium, 4 (2004). Merton College Register 1900-1964. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

^, BOMB, 58 (Winter 1997)., (London), 11 February 2014. Mike Berlin, 11 June 2009. Jonathan Derbyshire, 'Stuart Hall: 'We need to talk about Englishness',. Richard Paterson, Paul Gerhardt, BFI. Alex Callinicos, 'The politics of Marxism Today', International Socialism, 29 (1985). Retrieved 17 February 2014. Hudson, Rykesha (10 February 2014).

Retrieved 10 February 2014. The Daily Telegraph. 10 February 2014.

Butler, Patrick (10 February 2014). The Guardian. Procter 2004, p. Hall et al. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. ^ Scannell 2007, p. 211.

Scannell 2007, p. ^ Procter 2004, pp. Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse. Birmingham: Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, p. Hall 1973, p. Hall 1973, p. Hall 1973, p., Goldsmiths, University of London, 11 December 2014., The Voice, 4 December 2014., Tate Britain.

Mark Hudson, The Daily Telegraph (London), 15 October 2012. Clark, Ashley. 'Film of the Week: The Stuart Hall Project Sight & Sound'. British Film Institute.

29 September 2014. 24 November 2014. Jeffries, Stuart. 'Stuart Hall's Cultural Legacy: Britain under the Microscope.'

The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 10 February 2014. 24 November 2014. 'The Stuart Hall Project.' 24 November 2014.

Sut Jhally (30 August 2012). Retrieved 17 February 2014. Further reading. Chen, Kuan-Hsing (June 1986). 10 (2): 125–129.

Davis, Helen (2004). Understanding Stuart Hall. London: Sage. (June 1986). Journal of Communication Inquiry. 10 (2): 45–60. Grossberg, Lawrence (June 1986).

Journal of Communication Inquiry. 10 (2): 61–77. Grossberg, Lawrence;; Gilroy, Paul (2000). Without guarantees: in honour of Stuart Hall. London: Verso. (1998), 'Cultural identity and diaspora', in Rutherford, Jonathan, Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, London: Lawrence and Wishart, pp. 223–237,.

JBHE Foundation, Inc. Spring 2004.

External links.

Cultural studies: two paradigms Cultural studies: two paradigms STUART HALL from Media Culture and Society Volume 2, Number 1, January 1980. In serious, critical intellectual work, there are no 'absolute beginnings' and few unbroken continuities. Neither the endless unwinding of 'tradition', so beloved on the History of Ideas, nor the absolutism of the 'epistemological rupture', punctuating Thought into its 'false' and 'correct' parts, once favoured by the Althussereans, will do. What we find, instead, is an untidy but characteristic unevenness of development.

What is important are the significant breaks where old lines of thought are disrupted, older constellations displaced, and elements, old and new, are regrouped around a different set of premises and themes. Changes in a problematic do significantly transform the nature of the questions asked, the forms in which they are proposed, and the manner in which they can be adequately answered. Such shifts in perspective reflect, not only the results of an internal intellectual labour, but the manner in which real historical developments and transformations are appropriated in thought, and provide Thought, not with its guarantee of 'correctness' but with its fundamental orientations, its conditions of existence. It is because of this complex articulation between thinking and historical reality, reflected in the social categories of thought, and the continuous dialectic between 'knowledge' and 'power', that the breaks are worth recording.

Cultural Studies, as a distinctive problematic, emerges from one such moment, in the mid-1950s. It was certainly not the first time that its characteristic questions had been put on the table. Quite the contrary. The two books which helped to stake out the new terrain Hoggart's Uses of Literacy and Williams's Culture And Society were both, in different ways, works (in part) of recovery. Hoggart's book took its reference from the 'cultural debate', long sustained in the arguments around 'mass society, and in the tradition of work identified with Leavis and Scrutiny. Culture And Society reconstructed a long tradition which Williams defined as consisting, in sum, of 'a record of a number of important and continuing reactions to.

Changes in our social, economic and political life' and offering 'a special kind of map by means of which the nature of the changes can be explored' (p. The books looked, at first, simply like updating of these earlier concerns, with reference to the post-war world. Retrospectively' their 'breaks' with the traditions of thinking in which they were Situated seem as important, if not more so, than heir continuity with them. The Uses of Literacy did set outmuch in the spirit of 'practical criticism'to 'read' working class culture for the values and meanings embodied in its patterns and arrangements: as if they were certain kinds of 'texts'.

But the application of this method to a living culture, and the rejection of the terms of the 'cultural debate' (polarized around the high/low culture distinction) was a thorough-going departure. Culture and Society in one and the same movement-constituted a tradition ( the `culture-and-society tradition), defined its 'unity' (not in terms of common positions but in its characteristic concerns and the idiom of its inquiry), itself made a distinctive modern contribution and wrote its epitaph. The Williams book which succeeded it The Long Revolution clearly indicated that the 'culture-and-society' mode of reflection could be completed and developed by moving somewhere elseto a significantly different kind of analysis. The very difficulty of some of the writing in The Long Revolution - with its attempt to 'theorize' on the back of a tradition resolutely empirical and particularist in its idiom of thought, the experiential 'thickness' of its concepts, and the generalizing movement of argument in itstems, in part, from this determination to move on (Williams's work, right through to the most recent Politics And Letters, is exemplary precisely in its sustained developmentalism). The 'good' and the 'bad' parts of The Long Revolution both arise from its status as a work 'of the break'. The same could be said of E.

Thompson's Making Of The English Working Class which belongs decisively to this 'moment', even though, chronologically it appeared somewhat later. It, too, had been 'thought' within certain distinctive historical traditions: English marxist historiography, Economic and 'Labour' History.

But in its foregrounding of the questions of culture, consciousness and experience, and its accent on agency, it also made a decisive break: with a certain kind of technological evolutionism, with a reductive economism and an organizational determinism. Between them, these three books constituted the caesura out of which among other thing 'Cultural Studies' emerged. They were, of course, seminal and formative texts. They were not, in any sense, `text-books' for the founding of a new academic sub-discipline: nothing could have farther from their intrinsic impulse. Whether historical or contemporary in focus, they were, themselves, focused by, organized through and constituted responses to, the immediate pressures of the time and society in which they were written. They not only took 'culture' seriously as a dimension without which historical transformations, past and present, simply could not adequately be thought. They were, themselves, 'cultural' in the Culture And Society sense.

They forced on their readers' attention the proposition that 'concentrated in the word culture are questions directly by the great historical changes which the changes in industry, democracy and in their own way, represent, and to which the changes in art are a closely related response' (p. This was a question for the I960s and 70s, as well as the 1860s and 70s. And this is perhaps the point to note that this line of thinking was roughly coterminous with what has been called the 'agenda' of the early New Left, to which these writers, in one sense or another, belonged, and whose texts these were. This connection placed the 'politics of intellectual work' squarely at the centre of Cultural Studies from the beginning a concern from which, fortunately, it has never been, and can never be, freed. In a deep sense, the 'settling of accounts' in Culture And Society, the first part of The Long Revolution, Hoggart's densely particular, concrete of some aspects of working-class culture and Thompson's historical reconstruction of the formation of a class culture and popular traditions in the I790-I830 period formed, between them, the break, and defined the space from which a new area of study and practice opened. In terms of intellectual bearings and emphases if ever such a thing can be found Cultural Studies moment of 're-founding'. The institutionalization of Cultural Studies first, in the Centre at Birmingham, and then in courses and publications from a variety of sources and places with its characteristic gains and losses, belongs to the I960s and later.

`Culture was the site of the convergence. But what definitions of this core concept emerged from this body of work?

And, since this line of thinking has decisively shaped Cultural Studies, and represents the most formative indigenous or 'native' tradition, around what space was its concerns and concepts unified? The fact is that no single, unproblematic definition of 'culture' is to be found here. The concept remains a complex one a site of convergent interests, rather than a logically or conceptually clarified idea. This 'richness' is an area of continuing tension and difficulty in the field. It might be useful, therefore, briefly to resume the characteristic stresses and emphases through which the concept has arrived at its present state of (in)-determinacy. (The characterizations which follow are, necessarily crude and over-simplified, synthesizing rather than carefully analytic).

Two main problematics only are discussed. Two rather different ways of conceptualizing 'culture' can be drawn out of the many suggestive formulations in Raymond Williams's Long Revolution. The first relates 'culture' to the sum of the available descriptions through which societies make sense of and reflect their common experiences. This definition takes up the earlier stress on 'ideas', but subjects it to a thorough reworking. The conception of 'culture' is itself democratized and socialized. It no longer consists of the sum of the 'best that has been thought and said', regarded as the summits of an achieved civilization that ideal of perfection to which, in earlier usage, all aspired.

Even 'art' assigned in the earlier framework a privileged position, as touchstone of the highest values of civilization is now redefined as only one, special, form of a general social process: the giving and taking of meanings, and the slow development of 'common' meanings a common culture: 'culture', in this special sense, 'is ordinary' (to borrow the title of one of Williams's earliest attempts to make his general position more widely accessible). If even the highest, most refined of descriptions offered in works of literature are also 'part of the general process which creates conventions and institutions, through which the meanings that are valued by the community are shared and made active' (p.

55), then there is no way in which this process can be hived off or distinguished or set apart from the other practices of the historical process: 'Since our way of seeing things is literally our way of living, the process of communication is in fact the process of community: the sharing of common meanings, and thence common activities and purposes; the offering, reception and comparison of new meanings, leading to tensions and achievements of growth and change' (p. Accordingly, there is no way in which the communication of descriptions, understood in this way, can be set aside and compared externally with other things. 'If the art is part of society, there is no solid whole, outside it, to which, by the form of our question, we concede priority. The art is there, as an activity, with the production, the trading, the politics, the raising of families. To study the relations adequately we must study them actively, seeing all activities as particular and contemporary forms of human energy'.

If this first emphasis takes up and re-works the connotation of the term 'culture' with the domain of 'ideas', the second emphasis is more deliberately anthropological, and emphasizes that aspect of 'culture' which refers to social practices. It is from this Second emphasis that the somewhat simplified definition 'culture is a whole way of life, has been rather too neatly abstracted.

Stuart Hall Cultural Studies Two Paradigms

Williams did relate this aspect of the concept to the more 'documentary' that is, descriptive, even ethnographic usage of the term. But the earlier definition seems to me the more central one, into which way of life' is integrated. The important point in the argument rests on the active and indissoluble relationships between elements or social practices normally separated out.

It is in this context that the theory of culture is defined as the study of relationship between elements in a whole way of life'. 'Culture' is not a practice, nor is it simply the descriptive sum of the 'mores and folkways' of societies as it tended to come in certain kinds of anthropology. It is threaded through all social practices, and the sum of their inter-relationship.

The question of what, then, is studied, and how, resolves itself. The 'culture' is those patterns of organization, those characteristic forms of human energy which can be discovered as revealing themselves in unexpected identities and correspondences' as well as in 'discontinuities of an unexpected kind (p.

63)within or underlying all social practices. The analysis of culture is, then, 'the attempt to discover the nature of the organization which is the complex of these relationships'. It begins with 'the discovery of patterns of a characteristic kind'. One will discover them, not in the art, production, trading, politics, the raising of families, treated as separate activities, but through 'studying a general organization in a particular example' (p.

Analytically, one must study 'the relationships between these patterns'. The purpose of the analysis is to grasp how the interactions between all these practices and patterns are lived and experienced as a whole any particular period. This is its 'structure of feeling'. It is easier to see what Williams was getting at, and why he was pushed along this path, if we understand what were the problems he addressed, and what pitfalls he as trying to avoid.

This is particularly necessary because The Long Revolution (like any of Williams's work) carries on a submerged, almost 'silent' dialogue with alternative positions, which are not always as clearly identified as one would wish here is a clear engagement with the 'idealist' and 'civilizing' definitions of culture both the equation of 'culture' with ideas, in the idealist tradition; and the assimilation culture to an ideal, prevalent in the elitist terms of the 'cultural debate'. But there also a more extended engagement with certain kinds of Marxism, against which Williams definitions are consciously pitched. He is arguing against the literal operations of the base/superstructure metaphor, which in classical Marxism ascribed the domain of ideas and of meanings to the 'superstructures', themselves conceived merely reflective of and determined in some simple fashion by 'the base'; without a social effectivity of their own. That is to say, his argument is constructed against a vulgar materialism and an economic determinism.

He offers, instead, a radical interactionism: in effect, the interaction of all practices in and with one another, skirting the problem of determinacy. The distinctions between practices is overcome by seeing them all as variant forms of praxis of a general human activity and energy. The underlying patterns which distinguish the complex of practices in any specific society at any specific time are the characteristic 'forms of its organization' which underlie them all, and which can therefore be traced in each.

There have been several, radical revisions of this early position: and each has contributed much to the redefinition of what Cultural Studies is and should be. We have acknowledged already the exemplary nature of Williams's project, in constantly rethinking and revising older argumentsin going on thinking. Nevertheless, one struck by a marked line of continuity through these seminal revisions. One such moment is the occasion of his recognition of Lucien Goldmann's work, and through him, of the array of marxist thinkers who had given particular attention to supeructural forms and whose work began, for the first time, to appear in English translation in the mid-1960s. The contrast between the alternative marxist traditions which sustained writers like Goldman and Lukacs, as compared with Williams's isolated position and the impoverished Marxist tradition he had to draw on, is sharply delineated.

But the points of convergence- both what they are against, and what they are about are identified in ways which are not altogether out of line with his earlier arguments. Here is the negative, which he sees as linking his work to Goldmann's: 'I came to believe that I had to give up, or at least to leave aside, what I knew as the Marxist tradition: to attempt to develop a theory of social totality; to see the study of culture as the study of relations between elements in a whole way of life; to find ways of studying structure. Which could stay in touch with and illuminate particular art works and forms, but also forms and relations of more general social life; to replace the formula of base and superstructure with the more active idea of a field of mutually if also unevenly determining forces' (NLR 67, May-June 1971).

And here is the positive the point where the convergence is marked between Williams's 'structure of feeling' and Goldmann's 'genetic structuralism': 'I found in my own work that I had to develop the idea of a structure of feeling. But then I found Goldmann beginning.

From a concept of structure which contained, in itself, a relation between social and literary facts. This relation, he insisted, was not a matter of content, but of mental structures: 'categories which simultaneously organize the empirical consciousness of a particular social group, and the imaginative world created by the writer'. By definition, these structures are not individually but collectively created'. The stress there on the interactivity of practices and on the underlying totalities, and the homologies between them, is characteristic and significant.

'A correspondence of content between a writer and his world is less significant than this correspondence of organization, of structure'. A second such 'moment' is the point where Williams really takes on board E. Thompson's critique of The Long Revolution (cf. The review in NLR 9 and IO )that no 'whole way of life' is without its dimension of struggle and confrontation between opposed ways of life and attempts to rethink the key issues of determination and domination via Gramsci's concept of 'hegemony'.

This essay ('Base and Superstructure', NLR 82, 1973) is a seminal one, especially in its elaboration of dominant, residual and emergent cultural practices, and its return to the problematic of determinacy as 'limits and pressures'. None the less, the earlier emphases recur, with force: 'we cannot separate literature and art from other kinds of social practice, in such a way as to make them subject to quite special and distinct laws'. And, 'no mode of production, and therefore no dominant society or order of society, and therefore no dominant culture, in reality exhausts human practice, human energy, human intention'. And this note is carried forwardindeed, it is radically accentedin Williams's most sustained and succinct recent statement of his position: the masterly condensations of Marxism And Literature. Against the structuralist emphasis on the specificity and 'autonomy' of practices, and their analytic separation of societies into their discrete instances, Williams's stress is on 'constitutive activity' in general, on 'sensuous human activity, as practice', from Marx's first 'thesis' on Feuerbach; on different practices conceived as a 'whole indissoluble practice'; on totality. 'Thus, contrary to one development in Marxism, it is not 'the base' and 'the superstructure' that need to be studied, but specific and indissoluble real processes, within which the decisive relationship, from a Marxist point of view, is that expressed by the complex idea of 'determination' ' ( M & L, pp. At one level, Williams's and Thompson's work can only be said to converge around the terms of the same problematic through the operation of a violent and schematically dichotomous theorization.

The organizing terrain of Thompson's work classes as relations, popular struggle, and historical forms of consciousness, class cultures in their historical particularity - is foreign to the more reflective and generalizing mode in which Williams typically works. And the dialogue between them begins with a very sharp encounter. The review of The Long Revolution, which Thompson undertook, took Williams sharply to task for the evolutionary way in which culture as a 'whole way of life' had been conceptualized; for his tendency to absorb conflicts between class cultures into the terms of an extended 'conversation'; for his impersonal tone- above the contending classes, as it were; and for the imperializing sweep of his concept of 'culture' (which, heterogeneously, swept everything into its orbit because it was the study of the interrelationships between the forms of energy and organization underlying all practices. But wasn't this Thompson asked where History came in?) Progressively, we can see how Williams has persistently rethought the terms of his original paradigm to take these criticisms into account though this is accomplished (as it so frequently is in Williams) obliquely: via a particular appropriation of Gramsci, rather than in a more direct modification.

Thompson also operates with a more 'classical' distinction than Williams, between 'social being' and 'social consciousness' (the terms he infinitely prefers, from Marx, to the more fashionable 'base and superstructure'). Thus, where Williams insists on the absorption of all practices into the totality of 'real, indissoluble practice', Thompson does deploy an older distinction between what is 'culture' and what is 'not culture'. 'Any theory of culture must include the concept of the dialectical interaction between culture and something that is not culture.'